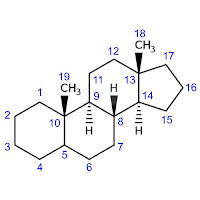

Here’s a molecule everybody must have heard about: testosterone (a).

|

| (a) |

|---|

|

We can try to name it systematically starting from the fused ring parent hydride 1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene (b):

|

| (b) |

|---|

|

The mancude structure (b) contains eight formal double carbon—carbon bonds while (a) has only one. To saturate seven double bonds of 1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene using organic additive nomenclature we need 14 hydrogens! That’s where the tetradecahydro bit is coming from. Substitution with –OH, two –CH3, and =O groups will give us hydroxy, dimethyl and one, respectively. We furnish the name with locants and stereodescriptors to get the final product: (1S,3aS,3bR,9aR,9bS,11aS)-1-hydroxy-9a,11a-dimethyl-1,2,3,3a,3b,4,5,8,9,9a,9b,10,11,11a-tetradecahydro-7H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-7-one. I bet you don’t like it*.

Alternatively, we can base the name on the fully saturated parent hydride (c) called androstane:

|

| (c) |

|---|

|

Note that the numbering of the structure (c) is totally different from that of (b).

To insert a double bond at the position 4, we treat androstane as we would any saturated hydrocarbon parent, viz. employing ‘an’ → ‘en’ operation. This will give us androst-4-ene. Substituting at the positions 3 and 17 with oxo and hydroxy groups, respectively, we get 17-hydroxyandrost-4-en-3-one.

Now let’s look at the stereochemistry. The parent structure (c) has five chiral carbons; testosterone (a) has six. The extra chiral centre results from substitution by a hydroxy group at the position 17. Of course, we can mark its configuration as ‘R’ or ‘S’ according to the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog (CIP) rules. However, in the world of steroids and other natural products, it’s more common to use the α/β convention.

First, we have to make sure that the ring system in question is oriented in the standard way. The standard orientation of steroids is such that the cyclopentane ring of the cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene (b) skeleton appears in the top right part of the diagram [2, 3S-1.4]. Now if an atom or group attached to the (properly oriented) ring system appears below it — that is, below the plane of the paper, or behind the plane of the computer screen displaying this structure — the configuration is denoted as ‘α’ (alpha); if the substituent is above this plane, the configuration is ‘β’ (beta)†. In the case of (a), the hydroxy group at C-17 is above the plane, so the full name will be 17β-hydroxyandrost-4-en-3-one.

That’s better, isn’t it? Not only is this name significantly shorter, it’s also easier to interpret. Instead of listing all 14 positions where we add hydrogens, we specify merely one where we put the double bond. And, since the parent structure has five built-in chiral centres, we have to include only one stereodescriptor, not six.

This simplicity comes at a price though. We can’t deduce what ‘androstane’ is from first principles: we have to look it up. Moreover, to use the α/β notation correctly, we should know the standard orientation of the parent structure. For example, given the InChI or SMILES string for (c), we can regenerate the corresponding 2-D structure but there’s no guarantee it will be in a standard orientation.

Androstane is a fundamental parent structure, or stereoparent [1, P-101.2.1.3]. IUPAC provides the list of recommended stereoparents and their structures in standard orientations [1, P-101.2.7].

The name ‘androstane’ implies the specific configurations of five chiral centres of (c): 8β, 9α, 10β, 13β and 14α‡. However, there is a sixth chiral atom, C-5. The α/β notation is used to specify the diastereomers 5α-androstane (d) and 5β-androstane (e):

|

|

| (d) | (e) |

|---|

|

To point out that the configuration of a chiral centre is unknown, the descriptor ‘ξ’ (xi) is used. Thus the structure (c) can be named 5ξ-androstane. Frankly, ‘ξ’ does not add much to the name but is a way to say “hey, we are aware that there is a chiral centre, we simply don’t know whether it’s ‘α’ or ‘β’”.

If configuration differs from that implied in the stereoparent, ‘α’ and ‘β’ are assigned to the corresponding chiral centres [1, P-101.2.6.1].

|

|

| (f) | (g) |

|---|

|

For instance, dydrogesterone (f) can be named semisystematically 9β,10α-pregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione. The ‘9β,10α’ bit indicates that the configurations of the C-9 and C-10 are inverted compared to the fundamental parent pregnane (g).

What if we need to invert all chiral centres in a molecule? Consider the structures (h) and (i):

|

|

| (h) | (i) |

|---|

|

The compound (h) is a fundamental parent known as kaurane. For its enantiomer (i), we can invert configurations at all chiral centres and name it (5β,8α,9β,10α,13α,16β)-kaurane. A shorter alternative is to call it ent-kaurane, with ‘ent’ being short for ‘enantio’ [1, P-101.8.1].

| * | Why, you might ask, we have ‘7H’ in (1S,3aS,3bR,9aR,9bS,11aS)-1-hydroxy-9a,11a-dimethyl-1,2,3,3a,3b,4,5,8,9,9a,9b,10,11,11a-tetradecahydro-7H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-7-one (a) if the parent structure is 1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene and, moreover, the structure (a) has exactly zero hydrogens at the position 7? Well, there is a rule that dictates to put the indicated hydrogens at peripheral atoms that will host principal characteristic groups [1, P-58.2.3.1]. In our case, we have the oxo group at C-7, so we move the indicated hydrogen there. It is as if we have started with a different tautomer of (b), viz. 7H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene: Since we add hydrogens to all carbon atoms of the ring system except C-5 and C-5a (we keep the double bond between them) and C-7 (oxo group there), the resulting string of fourteen locants is ‘1,2,3,3a,3b,4,5,8,9,9a,9b,10,11,11a’. Cf. the systematic name for androstane (c): (3aS,3bS,5aΞ,9aS,9bS,11aS)-9a,11a-dimethylhexadecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene. Here we start with 1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene and stay with ‘1H’. Because (c) is fully saturated, we don’t need any locants telling us where hydrogens are attached: just hexadecahydro is enough. The stereodescriptor ‘Ξ’ in ‘5aΞ’ shows that the configuration at C-5a is not defined. |

| † | I find it counterintuitive to assign ‘β’ to the atom or group that is closer to the viewer. To English speakers, ‘α’ (alpha) for above and ‘β’ (beta) for below would make a really good mnemonic. |

| ‡ | The same is true for other steroid fundamental parents [2, 3S-1.5]. |

References

- Favre, H.A. and Powell, W.H. Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations 2013 and Preferred IUPAC Names. Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, 2014.

- Moss, G.P. (1989) Nomenclature of steroids (Recommendations 1989). Pure and Applied Chemistry 61, 1783—1822.

No comments:

Post a Comment